Once every 27 million years (give or take an epoch), life on Earth takes

a bit of a battering from the cosmos. Asteroids, comets and other space

dwelling rocks strike the surface of the Earth, sending up clouds of

debris that wreak havoc with the climate, not to mention squashing

anything directly underneath. And this regularity has prompted various

theories throughout the ages, from asteroids from the asteroid belt

having unstable orbits, to long period comets somehow missing Jupiter

and colliding with Earth.

But one of the most plausible and yet most ridiculous being that the Sun has an evil twin - Nemesis.

Named for the Greek Goddess of Divine Retribution, the hypothetical

Nemesis would be a small red dwarf star. Red dwarves are the class of

star below our own Sun (which is a yellow dwarf), containing about 10%

of the mass and producing far less light. However, despite the name red

dwarves are not red, but a bright orange, roughly the same colour as

Fanta.

Nemesis would orbit the Sun at a distance of somewhere between 0.25 and 1

light years on a highly elliptical orbit. This orbit would place

Nemesis in the middle of a region known as the Oort Cloud, a vast region

containing most of the solar system’s comets. The presence of such a

star would knock comets out of their normal orbit, sending them into the

inner solar system where they might collide with one of the planets.

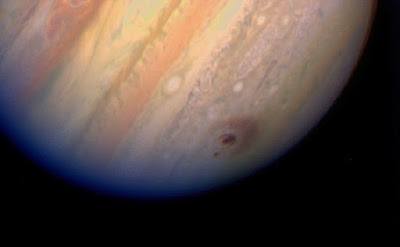

That comets come out of their natural habitat and seek out the planets

is not in question, and as recently as 1994 a large comet known as

Shoemaker-Levy collided with Jupiter, leaving a scar about the same size

as Earth. Even more recently (although less widely reported), another

object collided with Jupiter, leaving a scar merely the size of the

entire Pacific Ocean.

The Binary Research Institute

(BRI) has found that orbital characteristics of the recently discovered

planetoid, “Sedna”, demonstrate the possibility that our sun might be

part of a binary star system. A binary star system consists of two stars

gravitationally bound orbiting a common center of mass. Once thought to

be highly unusual, such systems are now considered to be common in the

Milky Way galaxy.

Walter Cruttenden at BRI, Professor

Richard Muller at UC Berkeley, Dr. Daniel Whitmire of the University of

Louisiana, amongst several others, have long speculated on the

possibility that our sun might have an as yet undiscovered companion.

Most of the evidence has been statistical rather than physical. The

recent discovery of Sedna, a small planet like object first detected by

Cal Tech astronomer Dr. Michael Brown, provides what could be indirect

physical evidence of a solar companion. Matching the recent findings by

Dr. Brown, showing that Sedna moves in a highly unusual elliptical

orbit, Cruttenden has determined that Sedna moves in resonance with

previously published orbital data for a hypothetical companion star.

In the May 2006 issue of Discover, Dr.

Brown stated: “Sedna shouldn’t be there. There’s no way to put Sedna

where it is. It never comes close enough to be affected by the sun, but

it never goes far enough away from the sun to be affected by other

stars… Sedna (Nemesis) is stuck, frozen in place; there’s no way to move

it, basically there’s no way to put it there — unless it formed there.

But it’s in a very elliptical orbit like that. It simply can’t be there.

There’s no possible way – except it is. So how, then?”

“I’m thinking it was placed there in the

earliest history of the solar system. I’m thinking it could have gotten

there if there used to be stars a lot closer than they are now and

those stars affected Sedna on the outer part of its orbit and then later

on moved away. So I call Sedna (Nemesis) a fossil record of the

earliest solar system. Eventually, when other fossil records are found,

Sedna will help tell us how the sun formed and the number of stars that

were close to the sun when it formed.”

Walter Cruttenden agrees that Sedna’s

highly elliptical orbit is very unusual, but noted that the orbit period

of 12,000 years is in neat resonance with the expected orbit

periodicity of a companion star as outlined in several prior papers.

Consequently, Cruttenden believes that Sedna’s unusual orbit is

something indicative of the current solar system configuration, not

merely a historical record.

“It is hard to imagine that Sedna would

retain its highly elliptical orbit pattern since the beginning of the

solar system billions of years ago. Because eccentricity would likely

fade with time, it is logical to assume Sedna is telling us something

about current, albeit unexpected solar system forces, most probably a

companion star”.

Outside of a few popular articles, and

Cruttenden’s book “Lost Star of Myth and Time”, which outlines

historical references and the modern search for the elusive companion,

the possibility of a binary partner star to our sun has been left to the

halls of academia. But with Dr. Brown’s recent discoveries of Sedna and

Xena, (now confirmed to be larger than Pluto), and timing observations

like Cruttenden’s, the search for a companion star may be gaining

momentum.

Unfortunately, there is absolutely no evidence that this star exists

as the theory predicts. Stars tend to be fairly visible objects (source:

the night sky) and the fact that this star cannot be demonstrably seen

does put a blow to the theory. As more powerful telescopes have searched

the sky, the scope for Nemesis being slightly too dim to detect have

diminished to the point that if it does exist, its nowhere near where

the theory puts it.

But like all evil twins, it is known by many names.

Tyche, the Greek Goddess of Fortune and Prosperity (and sister of

Nemesis) gives her name to the brown dwarf Tyche, not a star but a very

massive planet. Brown dwarfs are stars that never quite made it,

possessing insufficient mass to compress the hydrogen in their cores to

start nuclear fusion. Still, they would emit a lot of heat, and Tyche is

predicted to glow blood red as it weaves its way through deathbringer

comets. And this theory does has some (slight) evidence.

An object called Sedna, briefly called the 10th planet by the media

on its discovery, has an orbit that by all known laws should not be

possible. Its highly elliptical orbit is even at its closest twice as

far away as Pluto, but it never quite gets far away to belong to the

Oort Cloud either. The only explanation is that some other star must

have caused the impossible orbit. Tyche proponents suggest this as

evidence for a large planet, about five times the mass of Jupiter,

orbiting somewhere near the Oort cloud and pushing and pulling the small

rock in unpredictable ways. The other competing theory suggests that

the early solar system contained several stars in its interior, that

eventually coalesced into the Sun we see today. Sedna, the theory says,

would be a remnant of that era.

However, like Nemesis, Tyche has not been observed. Even though it

would not emit light in the same manner as a star, its proximity should

make its reflected light easily visible, and yet the sky contains no

such object

The theory seemed to be dead and buried, until just recently,

astronomers found a large object racing away from the sun. At a distance

of 20 light years, Scholz’s star is too distant to be bound to our Sun,

however by extrapolating its trajectory it has been discovered that

70,000 years ago, it must have passed through our solar system, coming

as close as 0.8 light years. This would put it not only bang in the

middle of the Oort cloud, but exactly where Nemesis/Tyche was predicted

to be. Upon further analysis, Scholz’s star was found to be a binary

system, consisting of a small red dwarf star, and a blood red brown

dwarf companion.

Perhaps there was something to the theory after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment